On Chatbots and Fairy-stories

This essay is on the two forms of escapism—one that flees reality, and one that leads more deeply into it.

In the 1960s, Joseph Ratzinger gave a series of lectures in which he described three faulty visions of the truth. The first, Verum quia cogitatum (“true because it is thought”), is exemplified by Descartes. It asserts that reality exists because one knows that it exists—making the initial shift to the subjective. The second, Verum quia faciens (“true because it is made”), is found in the thought of Giambattista Vico. Vico’s belief system emphasizes the limitations of our thought but also severs man from any immaterial truths. Only if man can replicate something in a laboratory, only if man can make it, can it be thought to be true—excluding love, justice, the immaterial soul, angels, and God. The third, Verum quia faciendum (“true because it must be made”), is attributed to the philosophy of Karl Marx. Truth, in this view, is that which must be made to change the world—truth is what is expedient. And here we hear the voice of Pilate , “Quid est veritas?” as throughout the Passion narrative, the Roman Governor never lies and yet is willing to sacrifice all truth to appease the chief priests and avoid trouble.

Of course these doctrines of belief and truth have each seen their day and none has truly been succeeded or abolished by the other. However, with the advent of artificial intelligence and the desire to delve deep into virtual realities, we should add a fourth vision of truth: Verum quia sentitur (“true because it is sensed”). Now, this vision of reality is nothing new. From David Hume to Ernst Mach to Jean Baudrillard, the emphaticism for empirical experience and the acceptance of replicated causes of sensation as good as the genuine cause of sensation itself marks a distinctly more substantive assault on truth than any of the other theories.

Indeed, while the other theories of truth reduce it to thinking, making, or doing, verum quia sentitur dissolves truth entirely into the flux of perception. It leaves us with not truth, but sensation—ever shifting, often curated, and easily manipulated. And to those who embrace this vision of truth, sensation is preferable to reality. And when sensation is preferable to reality, the goal is to escape reality—which tragically has been made manifest in the suicides of those children, like Sewell Setzer III who killed himself in 2024 so that he could “go home” to his AI chatbot girlfriend.

This reduction of truth to curated sensation has long been explored and anticipated in literature . Perhaps no image captures it better than the life of Des Esseintes, the anti-hero of J.K. Huysmans’s decadent novel À Rebours (sometimes rendered into English, Against Nature). The book was received as a kind of bible among the decadent movement—Oscar Wilde among them—precisely for its portrayal of artifice elevated above reality.

In the novel, Des Esseintes builds a dining room that resembled the cabin of a ship, with its ceiling of arched beams, its bulkheads and floorboards of pitch-pine, and a little window opening, let into the wainscotting like a porthole. Behind the window he placed a large aquarium with mechanical fish and seaweed with a genuine window placed in the outer wall, so that the light, to brighten the room, would have to traverse the window, the water, and, lastly, the window of the porthole. By these means, the character was able to “enjoy quickly, almost simultaneously, all the sensations of a long sea-voyage, without ever leaving home… The imagination could provide a more than adequate substitute for the vulgar reality of actual experience.”

In such a world—a world of sensation first—knowledge does not begin in the senses; the senses are all there is. Sensation, at its core, only becomes pleasure or pain—there is nothing beyond that, no cause of sensation worth knowing. There is no symbiosis between man and his environment, no right order, merely the need to conform sensory experience to one’s desires.

The idea of a virtual reality—from Des Esseintes to ChatGPT—is escapist in the worst possible sense. And there are different ways of understanding escapism.

Man is a microcosm. Because of his bodily nature, he has something in common with the beasts, and because of his immaterial soul, he shares something with the divine. He is torn between the appetites of his animal nature and the aspirations of his rational soul—and escapism, in its two forms, seeks to tip the balance one way or the other.

When J.R.R. Tolkien was asked to be the Andrew Lang Lecturer at the University of Scotland, he wrote what is called On Fairy-Stories, in which he tells us that a fairy story is escapist, but in the truest way, in the way, a man wrongly imprisoned must escape.

The word fantasy itself clues us into this truth behind good fiction, for fantasy comes from the Greek verb phainein, “to shine.” Fantasy is meant to bring light into the reader's mind, which assumes the one reading is in some darkness—which, of course, all of us are, as Paul tells us in 1 Corinthians 13:12.

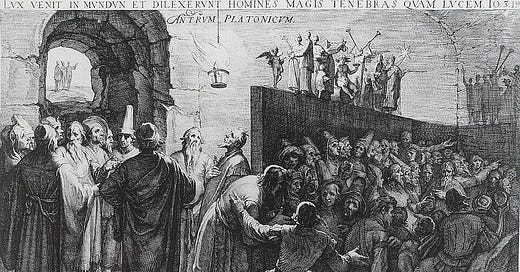

Although Tolkien is known for having expressed his reservations toward allegory, it is hard not to think of one that most aptly applies to the escapist teleology of fantasy, Plato’s allegory of the cave. In the allegory of the cave, man is in ignorance, and he mistakes shadows of animals and plants for the real thing. But, when one of the imprisoned escapes, he is brought into the light and begins to realize that all of what he had experienced in the cave were phantoms, only images of the real world.

Today, we are less in darkness and rather more in raving light—it is not an absence of sense experience, but an excess that blinds us. Man by nature desires to know, but if he satisfies this desire with constant stimulation, from music to television to TikTok, he may scorn the teachers of real wisdom when he encounters them. Learning may be painful, but as Proverbs 27:7 says, “He who is sated loathes honey, but to one who is hungry, everything bitter is sweet.” If we satiate our minds with constant stimulation, how will we ever be hungry enough to go through the pain of learning?

For the human eye to see clearly, the shadows cannot be too deep nor the light overwhelming. By nature, we need a balance between light and darkness for our eyes to perceive anything. So, too, is it with the intellect.

The arts, when understood as an imitation of nature, should spur the appetite for reality and, more importantly, the source of all reality; it should not try to satisfy it. Of course, real beauty can exist in both art and nature, but most properly, it is the task of philosophers and theologians in this life to find Truth, and it is the ultimate gift in eternal life, the Beatific Vision.

In Aristotle’s Metaphysics, we are told that the philomythos (the lover of myth) is something of a philosopher (lover of wisdom). This similarity is because, in myth, wonder is ignited. Wonder is not ignorance or simple curiosity; instead, wonder is the desire to know the principles and causes of things. And, it is the wise man who knows these things and wonders at the source of them: God.

The malaise so deeply felt by people, young and old, in our society might very well be a result of our attempts to separate sense from the cause of sensation, effectively attempting to escape reality. Sexual pleasure without sex (or with the same sex), pride without accomplishment, adventure without leaving one's couch is something we all intuitively understand to be wrong.

In a sense, the original “sin” of those living in Plato’s cave was believing that the temporal goods of this life—our land, our money, our foods—were the true sources of happiness. Yet today, men have even been fooled into spending money on virtual money, money that exists within a game, a virtual money that only allows one to buy one’s virtual character food, shelter, or companionship.

In his letter to the Romans, St. Paul writes that God’s “power and deity has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made…” but the wise became foolish for exchanging “the glory of the immortal God for the images resembling” Him and, thus “they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator.” What would St. Paul say of a society that worships the makings of the creature, rather than the creature—not to mention giving not a thought to the Creator?

All of this might seem to point out that the natural end of man is to seek a satisfaction for his desires among those finite things that exist proportionate to himself. However, man by nature being caught in the middle between beast and god attempts to escape from this natural state of things, and there are two roads that he can take. These roads are the two types of escapism. The first, the sort of Des Esseintes, is that which tries to escape reality and live only by the senses. This first road is the path to a beastly existence and isolation. Indeed, in his Untimely Meditations, Nietzsche points out this sort of life as the life of an animal—a life that makes man envy the cows for their gaiety—a life isolated, complete in its lack of memory, like a number without awkward fraction or anticipation—a happiness of ignorance.

The second road, however—the escapism of fairy stories, good music, and other arts—is that which recognizes that what changes from state to state is in danger of losing any good it has laid hold onto at any moment. It is the road that recognizes the unchanging—that is, thing that stands in no danger of losing the good it has possessed—as the summit to strive toward. For only in stability is their rest. The second road does not deny the flux and change of life, but it recognizes that the road is a road to someone and that we live in this land of shadows as pilgrims in this life, citizens of the heavenly Kingdom, and our Truth is unchanging, pure, and immortal (Matthew 6:19-21).

Knowledge does, in fact, begin in the senses but it does not end there. Those who live their lives through the internet or with AI chatbots, as modern-day Des Esseintes, do not love their life—they never move past the beginning of the experience. Instead, they become recluses and what they escape is not reality but their minds. Whereas those who experience the experience, and by experience build memories, intuitions, and ultimately come to knowledge—those are the ones who truly live. They are the ones who, through wonder, begin to seek not merely sensation but meaning, not the images (icons) but the reality to which those images point.

It is this second kind of escapism—the true kind—that Peter commends in his second epistle: “For by these [knowledge of Christ’s glory and excellence] He [i.e., God] has granted to us His precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world because of lust.” This is not an escape from reality, but an escape into it. It is the flight of the soul from shadow to substance, from the flickering images of this world to the solid joy of the world to come. In the end, all other forms of escapism abandon the mind to illusion. But this one—this holy upward escape—transfigures the mind, and leads it to God.

Thank you for reading.

Thanks for this article. Just a little clarification: “verum quia factum” is the phrase for the distinction that Vico offered - which wasn’t his “baby” really, but just a helpful way to classify a then modern tendency in thought.

Then there is “verum quia sentitur”. Careful with the spelling because senitur would be a bit different!

God bless.

Des Esseintes is a Wes Anderson character.