What Cannot Be Taken Away: Cassian, Prayer, and the Presence of Christ

John Cassian’s Conferences reveal how prayer, detachment, and the Eucharist guide the Christian from earthly tools to divine union.

At the end of Benedict’s Rule, the Father of Western monasticism recommends two authors for further reading. One is Basil the Great’s work on the ascetic life, and the other is John Cassian’s works. The reason for this is both Fathers, were able to articulate the proper ordering and use of the things of this world, and how to direct them toward life in the next. In this essay, I want to focus on John Cassian and his teachings in the Conferences.

The Conferences are a series of recorded conversations, between Cassian, his companions, and various holy men who lived in the desert. To understand these teachings, we will look at the Christian life in general, the goals of perfection, and the path to this perfection via ascetism and prayer. I will also reference other authors, such as Augustine, to further illustrate some of the arguments from Cassian.

In John Cassian’s first conference, the basic outline for the Christian life is laid out in two major ways. In the first, the Abbot speaking tells Cassian that theology—or the life of a monk—is no different than any other science. At root, the goal is to discover the principles and causes of a life of holiness, and this ultimately finds its source in the Godhead. The principles and causes, then, are understood in terms of the dual command of Christ: to love God above all things and to love one’s neighbor as oneself.

We are told that these two commands were exemplified by the characters of Martha and Mary in Luke’s Gospel. Where Martha was intent of serving the Lord in material things, Mary sat at the foot of our Lord to learn of things Divine. Martha by no means chose anything base or unpraiseworthy, however, Christ rebukes her to say that Mary had chosen the “better part;” the part which would not be taken away from her.

The reason for this part being the better one is because, while the two parts combine to make a whole in this temporal life, the temporal life is aimed at the splendor of the eternal one. St. Augustine, in his On Christian Doctrine, illustrates this point well when he gives the analogy of a pilgrim traveling home. In Augustine’s analogy, we are like pilgrims on our way to our homeland. The ship, the sea, the mountains, and the villages we pass through are all good insofar as they help us attain our goal.

However, if the pilgrim traveling through these beautiful places lingered or began to forget his homeland, where the fulness of his life resided, we would consider this man to have erred (from errare, meaning “to wander”). Likewise, while Martha works in service of her neighbor—exemplifying the corporeal works of mercy—we should recognize that our true love of neighbor can only be fulfilled if we seek to bring each other into that Divine splendor of beatific contemplation.

In the ninth conference, John Cassian gives us another example of this when he discusses the four types of prayer. We learn that prayer can be considered under the aspect of supplication, prayer, intercession, and thanksgiving. Three of these—supplication, intercession, and thanksgiving—are often directed to things of this life.

However, the one called prayer, where one offers something to God is most appropriately called “prayer” because it embodies the part that will not be taken away, i.e., our complete self-offering to God. In fact, this “self-offering” is in large part the topic of book X of Augustine’s City of God, in which he distinguishes the true love of the angels who wish us to find our blessedness in bringing our contrite heart to God instead of offering ourselves as servants to themselves, as the demons demand.

Throughout the course of the Conferences, the complete self-offering of a contrite heart is seen as a summit of the monastic life, and consequently it cannot be considered the start.

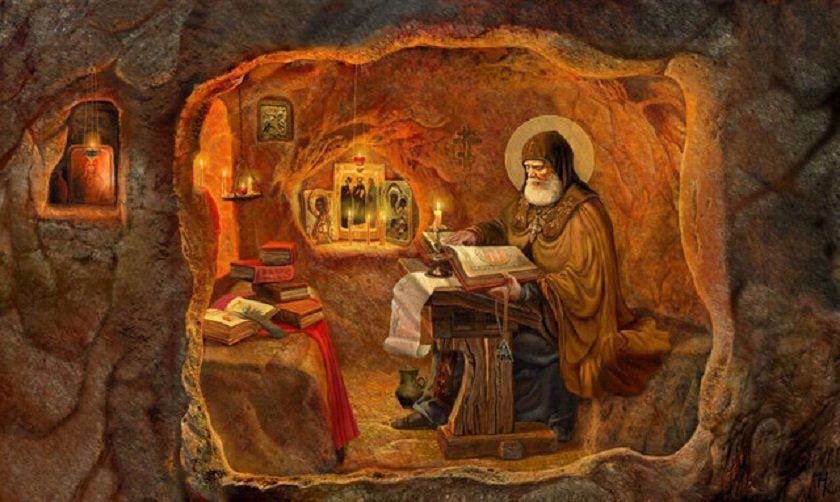

In Conference 10 and 11, the idea of a correct ordering is discussed. In fact, on the essential aspects on the path to the holiness is a correct understanding of the Divine. John Cassian gives the example of the monk Serapion, who held in his mind an image of God the Father based on the anthropomorphisms of the Old Testament. When, by a letter from the bishop of Alexandria, these anthropomorphisms are condemned, the monk Serapion is said to have been distraught and cried, “you have taken my god from me.”

In Conference 14, we are taught that such aids (images from scripture and icons) to the spiritual life cannot be considered as ends in themselves. In this context, how one discerns between intrinsic and contextual evils is elaborated. For example, the monk in dialogue with Cassian explains that when we abstain from one thing it does not mean its opposite is evil. His proof for this claim is that when we abstain and fast from food, we cannot say that eating is evil. Instead, the use and abstinence of all good things is meant to bring us along on our journey to blessedness.

In this way, it becomes clear that visual aids—such as those used by Serapion—may be useful so long as they point to that which they are an image of, but should they become the sole object of our enjoyment, then we are making them idols for ourselves. Like Serapion’s over attachment to his imagined god, if any person is overly attached to the food they eat or even to the act of abstaining (to the point of grave illness), then one is making an idol of the tools for sanctity.

That one can make an idol of the tools for sanctity is further illustrated in Conference 21, where we learn that “Only God is good.” Following this notion, it is understood that each of the good things which God creates, He has created and left for us to be used to bring us—the monk—to the ultimate enjoyment of that which alone can be enjoyed in itself, God himself.

This likewise finds articulation in St. Augustine’s On Christian Teaching and book X of the City of God. In both of these works, we learn the distinction between loving something for its own sake and loving something as a means. Augustine is clear in this world and the next, nothing can be loved for its own sake except for God. God, Himself, only loves Himself for his own sake, and we are loved as means for His glory. The rational behind this is clear, since God is the source of light what need does the source have for the objects that only reflect him?

In another conference, again the monk tells us that we ought to be entirely detached from those things of this world in favor of the next.

To illustrate this, he tells a story of a monk who took up his hermitage nearby the town he grew up. After two decades of solitude, his younger brother came to him to ask for help getting an ox out of the mud. The monk responded by asking why the younger brother did not ask their other brother who lived closer to the town to help him. The younger brother responded to the monk saying that their brother had been dead for fifteen years, to which the monk said, “Do you not know that I too have been dead to this world for twenty years and can no more leave my tomb than he?”

The story well illustrates that, while not fully despising life or the body, we as pilgrims journeying to the eternal home must die completely to the cares of this “earthly kingdom” so as to hurry onward to the heavenly one.

As if to put two bookends on the Conferences, in the penultimate conference, we are reminded of Martha and Mary again and how they represent those two halves of the Christian life. And yet, in the final conference, we are given an explicit teaching on the Eucharist which completes the discussion on holiness—since to be with God is something even accessible for us in this life.

The monk, in the final conference, explains that communion with the Divine is the absolute end goal of all prayer and asceticism, but Jesus Christ as mediator has made himself the ultimate means by which we attain the goal. In fact, communion with Jesus Christ is both means and goal, and as a result the monk warns that no one should wait to receive the Eucharist until they have reached perfection since that is not something one can discern in the first place, and in the second, the Eucharist is the living bread which gives us life.

Throughout the Conferences, there are many wonderful stories that illustrate this journey to holiness. From prayer and fasting to the ultimate contemplation and communion with the Divine, John Cassian illustrates that the Christian life on this earth is a pilgrimage. However, the final conference, with its emphasis on the Eucharist, gives us the ultimate destination and christocentrism, which is central to the Christian message. Indeed, this is also very much the subject which St. Augustine articulated in his City of God, that Christ is the only true mediator between God and man. That Christ is the mediator, who comes to the earthly state which is lowly, mortal, and miserable, and by his diverse medicines brings us to a life in communion with him which is lofty, eternal, and blessed.

Saint John Cassian, pray for us! 🌍🇹🇩☦️⛪📚✍🏼

(skopos / telos ~ Mt. 5:8)